Lily JamaliTechnology correspondent, San Francisco

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt OpenAI’s DevDay this week, OpenAI boss Sam Altman did what American tech bosses rarely do these days: he actually answered questions from reporters.

“I know it’s tempting to write the bubble story,” Mr Altman told me as he sat flanked by his top lieutenants. “In fact, there are many parts of AI that I think are kind of bubbly right now.”

In Silicon Valley, the debate over whether AI companies are overvalued has taken on a new urgency.

Sceptics are privately – and some now publicly – asking whether the rapid rise in the value of AI tech companies may be, at least in part, the result of what they call “financial engineering”.

In other words – there are fears these companies are overvalued.

Mr Altman said he expected investors would make some bad calls and silly start-ups would walk away with crazy money.

But with OpenAI, he told me, “there’s something real happening here”.

Not everyone is convinced.

In recent days, warnings of an AI bubble have come from the Bank of England, the International Monetary Fund, as well as JP Morgan boss Jamie Dimon who told the BBC “the level of uncertainty should be higher in most people’s minds”.

And here, in what is often considered the tech capital of the world, concerns are growing.

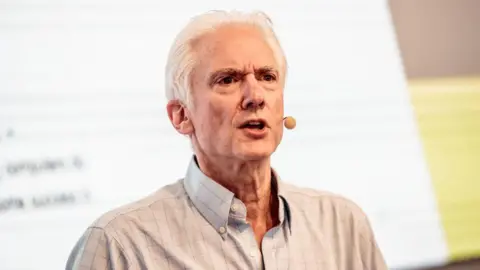

At a panel discussion at Silicon Valley’s Computer History Museum this week, early AI entrepreneur Jerry Kaplan told a packed audience he has lived through four bubbles.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe’s especially concerned now given the magnitude of money on the table as compared to the dot-com boom. There’s so much more to lose.

“When [the bubble] breaks, it’s going to be really bad, and not just for people in AI,” he said.

“It’s going to drag down the rest of the economy.”

However, at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, which has minted its fair share of tech entrepreneurs, Prof Anat Admati says while there have been many attempts to model when we’re in the bubble, it can be a futile exercise.

“It is very hard to time a bubble,” Prof Admati told me. “And you can’t say with certainty you were in one until after the bubble has burst.”

But the data is concerning to many.

AI-related enterprises have accounted for 80% of the stunning gains in the American stock market this year – and Gartner estimates global spending on AI will likely reach a whopping $1.5tn (£1.1tn) before 2025 is out.

Tangled web of deals

OpenAI, which brought AI into the consumer mainstream with ChatGPT in 2022, is at the centre of the tangled web of deals drawing scrutiny.

For example – last month, it entered into a $100bn deal with chipmaker Nvidia, which is itself the most valuable publicly traded company in the world.

It expands an existing investment Nvidia already had in Mr Altman’s company – with expectations that OpenAI will build data centres powered with Nvidia’s advanced chips.

Then on Monday, OpenAI announced plans to purchase billions of dollars worth of equipment for developing AI from Nvidia rival AMD, in a deal that could make it one of AMD’s largest shareholders.

Remember this is a private company, albeit one recently valued at a half-trillion dollars.

Then there’s tech giant Microsoft, which is heavily invested, and cloud computing behemoth Oracle has a $300bn deal with OpenAI, too.

OpenAI’s Stargate project in Abilene, Texas, funded with the help of Oracle and Japanese conglomerate SoftBank and announced at the White House during President Donald Trump’s first week in office, grows ever larger every few months.

And as for Nvidia, it has a stake in AI startup CoreWeave – which supplies OpenAI with some of its massive infrastructure needs.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd as these increasingly complex financing arrangements get more and more common, the experts here in Silicon Valley say they may be clouding perceptions on AI demand.

Some people aren’t mincing their words about it either, calling the deals “circular financing” or even “vendor financing” – where a company invests in or lends to its own customers so they can continue making purchases.

“Yes, the investment loans are unprecedented,” Mr Altman told me on Monday.

But, he added, “it’s also unprecedented for companies to be growing revenue this fast.”

OpenAI’s revenue is growing quickly, but it has never turned a profit.

And it is hardly a good sign that the people I’ve spoken to keep bringing up Nortel – the Canadian telecom equipment-maker that borrowed prolifically to help finance deals for their customers (and thereby artificially boost demand for their wares).

For his part, Nvidia’s Jensen Huang defended his deal with OpenAI on CNBC Monday, saying the firm isn’t required to buy his company’s tech with the money he invests.

“They can use it to do anything they like,” Huang said.

“There’s no exclusivities. Our primary goal is just really to support them and help them grow – and grow the ecosystem.”

Telltale signs

Mr Kaplan says he sees a couple of telltale signs the AI sector – and therefore the wider economy – could be in trouble.

In frothy times, he says, companies announce major initiatives and product plans that they don’t yet have the capital for.

Meanwhile, retail investors clamour to get in on the start-up action.

The surge in AMD stock this week could indicate investors are trying to get a piece of the ChatGPT wealth machine – and while all this is playing out, real physical infrastructure aimed at satisfying the seemingly insatiable hunger for more AI development is being built.

“We’re creating a new man-made ecological disaster: enormous data centres in remote places like deserts, that will be rusting away and leaching bad things into the environment, with no one left to hold accountable because the builders and investors will be long gone,” Mr Kaplan said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut even if we are in a bubble, the hope from Silicon Valley is investments being made now won’t necessary go to waste.

“The thing that comforts me is that the internet was built on the ashes of the over-investment into the telecom infrastructure of yesterday,” said Jeff Boudier, who builds products at the AI community hub Hugging Face.

“If there is overinvestment into infrastructure for AI workloads, there may be financial risks tied to it,” he said.

“But it’s going to enable lots of great new products and experiences including ones we’re not thinking about today.”

There are plenty of believers in AI’s potential to transform society.

The question is whether the money to fund the ambitions of the foremost companies in the sector may be drying up.

“Nvidia looks like the last lender or investor,” said Rihard Jarc, who founded the UncoverAlpha newsletter.

“Who else has the capacity right now to invest $100 billion in another company?”